Babe Ruth

Babe Ruth

United States of America

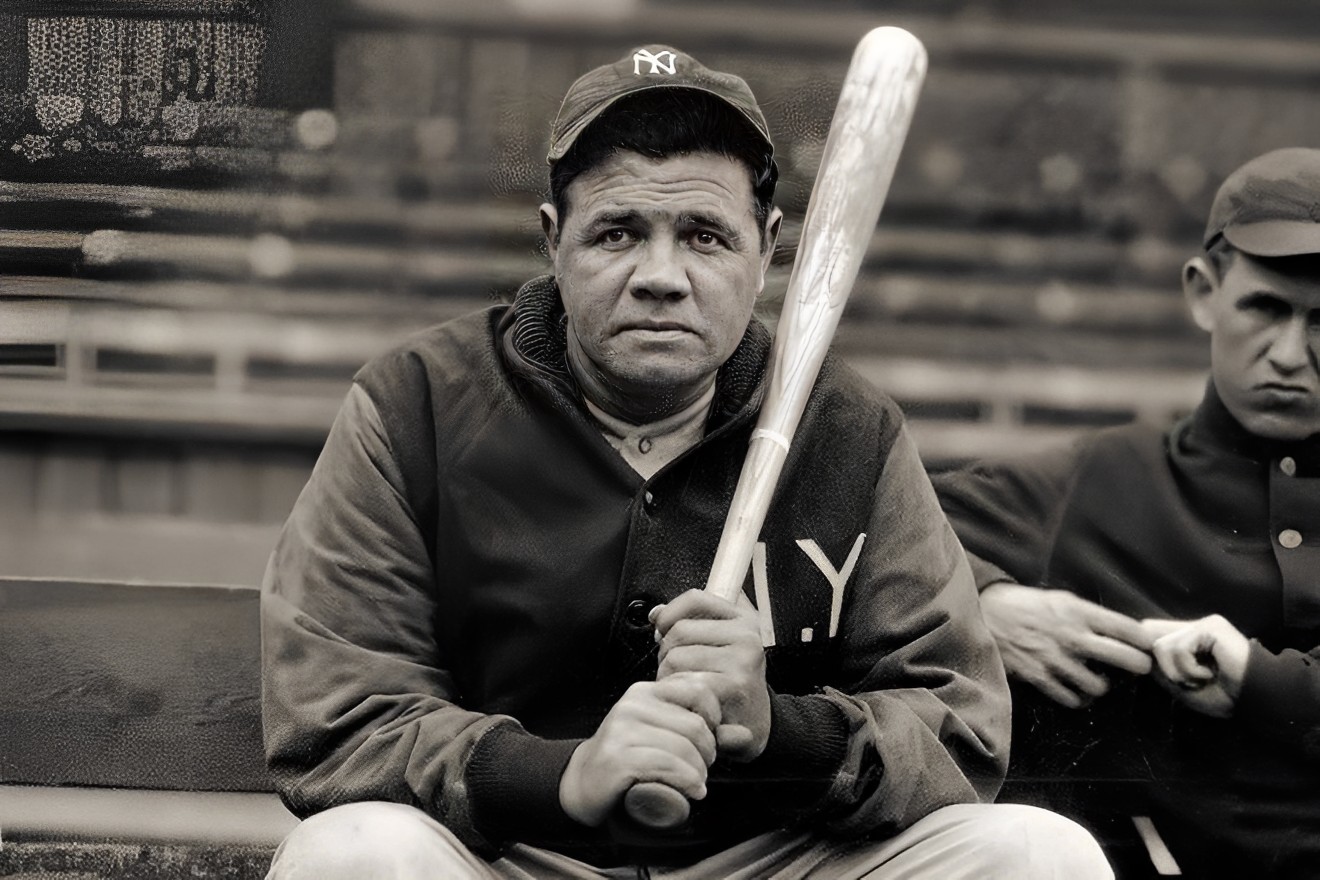

United States of AmericaBabe Ruth, byname of George Herman Ruth, Jr., also called the Bambino and the Sultan of Swat, (born February 6, 1895, Baltimore, Maryland, U.S.—died August 16, 1948, New York, New York), American professional baseball player. Largely because of his home-run hitting between 1919 and 1935, Ruth became, and perhaps remains to this day, America’s most celebrated athlete.

Part of the aura surrounding Ruth arose from his modest origins. Though the legend that he was an orphan is untrue, Ruth did have a difficult childhood. Both his parents, George Herman Ruth, Sr., and Kate Shamberger Ruth, came from working-class, ethnic (German) families. Ruth, Sr., owned and operated a saloon in a tough neighbourhood on the Baltimore waterfront. Living in rooms above the saloon, the Ruths had eight children, but only George, Jr., the firstborn, and a younger sister survived to adulthood. Since neither his busy father nor his sickly mother had much time for the youngster, George roamed the streets, engaged in petty thievery, chewed tobacco, sometimes got drunk, repeatedly skipped school, and had several run-ins with the law. In 1902 his parents sent him to the St. Mary’s Industrial School for Boys, a Baltimore, Maryland, asylum for incorrigibles and orphans run by the Xaverian Brothers order of the Roman Catholic Church. For the next 10 years Ruth was in and out of St. Mary’s. When his mother died from tuberculosis in 1912, he became a permanent ward of the school.

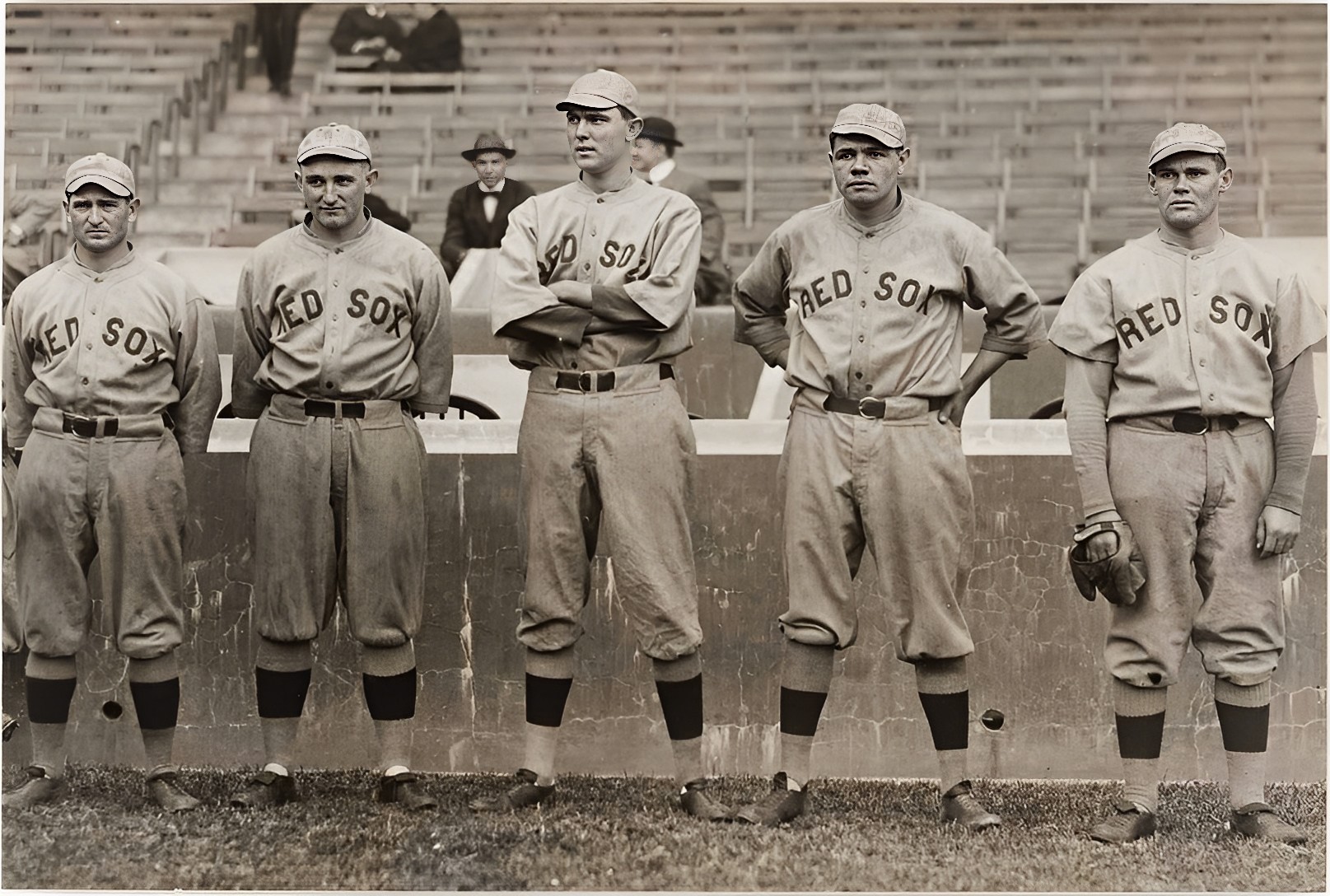

Baseball offered Ruth an opportunity to escape both poverty and obscurity. While a teenager at St. Mary’s, he achieved local renown for his baseball-playing prowess, and in 1914 Jack Dunn, owner of the local minor-league Baltimore Orioles franchise, signed him to a contract for $600. Ruth obtained the nickname “Babe” when a sportswriter referred to him as one of “Dunn’s babes.” For his day, Ruth was a large man; he stood more than six feet tall and weighed more than 200 pounds. Before the end of the 1914 season, his performance as a pitcher was so impressive that Dunn sold Ruth to the American League Boston Red Sox. That same year Ruth met, courted, and wed waitress Helen Woodford. Ruth soon became the best left-handed pitcher in baseball. Between 1915 and 1919 he won 87 games, yielded a stunning earned run average of only 2.16, won three World Series games (one in 1916 and two in 1918), and, during a streak for scoreless World Series innings, set a record by pitching 29 2/3 consecutive shutout innings.

At the same time, Ruth exhibited so much hitting clout that, on the days he did not pitch, manager Ed Barrow played him at first base or in the outfield. In an age when home runs were rare, Ruth slammed out 29 in 1919, thereby topping the single-season record of 27 set in 1884 (by Ned Williamson of the Chicago White Stockings). In 1920 Harry Frazee, the team owner and a producer of Broadway plays who was always short of money, sold Ruth to the New York Yankees for $125,000 plus a personal loan from Yankee owner Jacob Ruppert. While initially reluctant to leave Boston, Ruth signed a two-year contract with the Yankees for $10,000 a year.

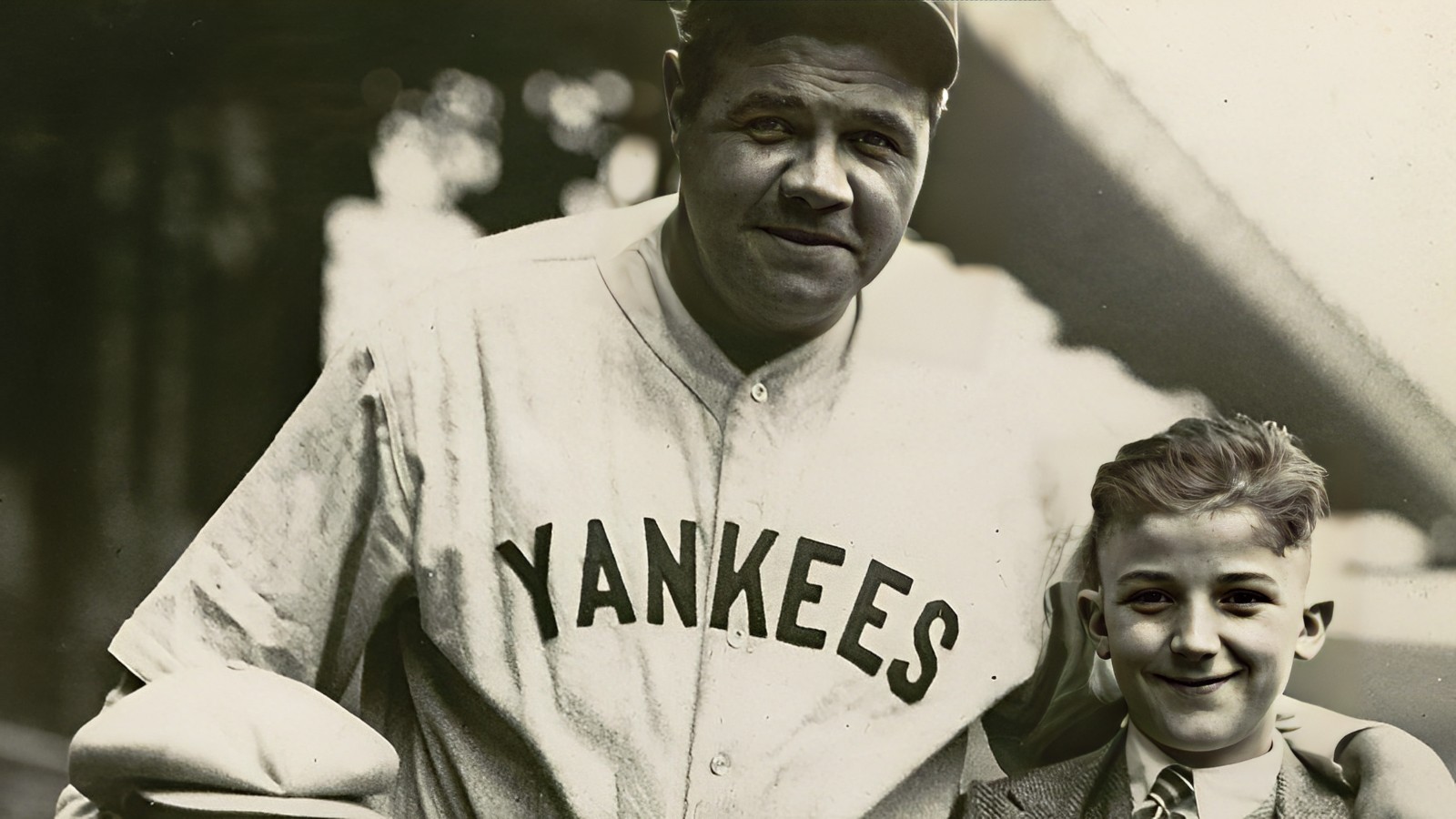

New York Yankees

As a full-time outfielder with the Yankees, Ruth quickly emerged as the greatest hitter to have ever played the game. Nicknamed by sportswriters the “Sultan of Swat,” in his first season with the Yankees in 1920, he shattered his own single-season record by hitting 54 home runs, 25 more than he had hit in 1919. The next season Ruth did even better: he slammed out 59 homers and drove in 170 runs. In 1922 his salary jumped to $52,000, making him by far the highest-paid player in baseball. That summer he and Helen appeared in public with a new daughter, Dorothy, who was apparently the result of one of his many sexual escapades.

In 1922 Ruth’s home run totals dropped to 35, but in 1923—with the opening of the magnificent new Yankee Stadium, dubbed by a sportswriter “The House That Ruth Built”—he hit 41 home runs, batted .393, and had a record-shattering slugging percentage (total bases divided by at bats) of .764. He continued with a strong season in 1924 when he hit a league-leading 46 home runs, but in 1925, while suffering from an intestinal disorder (thought by many to be syphilis), his offensive production declined sharply. That season, while playing in only 98 games, he hit 25 home runs.

He also struggled in his private life. Two years earlier he had met and fallen in love with actress Claire Hodgson, and in 1925 he legally separated from Helen. Helen’s death from a fire in 1929 freed him to marry Hodgson the same year. The couple then formally adopted Dorothy, and Ruth adopted Hodgson’s daughter, Julia.

On the field during the 1926 season, Ruth returned to his old form. Indeed, in the 1926–32 seasons Ruth in his offensive output towered over all other players in the game. For those seven seasons he averaged 49 home runs per season, batted in 151 runs, and had a batting average of .353 while taking the Yankees to four league pennants and three World Series championships. In 1927 Ruth’s salary leapt to $70,000. That season he hit 60 home runs, a record that remained unbroken until Roger Maris hit 61 in 1961 (see also Researcher’s Note: Baseball’s problematic single-season home run record). That same season Ruth teamed with Lou Gehrig to form the greatest home-run hitting duo in baseball. Ruth and Gehrig were the heart of the 1927 Yankees team—nicknamed Murderer’s Row—which is regarded by many baseball experts as the greatest team to ever play the game.

The 1932 World Series revealed not only Ruth’s flair for exploiting the moment but produced his famous “called shot” home run. In the third game of the series against Chicago, while being heckled by the Cubs bench, Ruth, according to a story whose accuracy remains in doubt to this day, responded by pointing his finger to the centre-field bleachers. On the very next pitch, Ruth hit the ball precisely into that spot. After 1932 Ruth’s playing skills rapidly diminished. Increasingly corpulent and slowed by age, his offensive numbers dropped sharply in both 1933 and 1934. He wanted to manage the Yankees, but Ruppert, the team’s owner, is reported to have said that Ruth could not control his own behaviour, let alone that of the other players, and so refused to offer him the post. Hoping eventually to become a manager, in 1935 Ruth joined the Boston Braves as a player and assistant manager. But the offer to manage a big-league team never came. Ruth finished his career that season with 714 home runs, a record that remained unblemished until broken by Henry Aaron in 1974.

In 1936 sportswriters honoured Ruth by selecting him as one of five charter members to the newly established Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, New York. Ruth was a hopeless spendthrift, but, fortunately for him, in 1921 he met and employed Christy Walsh, a sports cartoonist-turned-agent. Walsh not only obtained huge contracts for Ruth’s endorsement of products but also managed his finances so that Ruth lived comfortably during retirement. During his final years Ruth frequently played golf and made numerous personal appearances on behalf of products and causes but missed being actively involved in baseball. Still, he maintained his popularity with the American public; after his death from throat cancer, at least 75,000 people viewed his body in Yankee Stadium, and some 75,000 attended his funeral service (both inside and outside St. Patrick’s Cathedral).

Ruth was a major figure in revolutionizing America’s national game. While the frequent claim that his feats single-handedly saved the game from a massive public disillusionment that might have otherwise accompanied the Black Sox Scandal of 1919 is an exaggeration, his home-run hitting did revitalize the sport. Prior to Ruth, teams had focused on what they called “scientific” or “inside” baseball—a complicated strategy of employing singles, sacrifices, hit-and-run plays, and stolen bases in order to score one run at a time. But Ruth seemed to make such tactics obsolete; with one mighty swat, he could clear the bases. While no other player in his day compared to Ruth in the ability to hit home runs, soon other players were also swinging harder and more freely. Indeed, Ruth helped to introduce an offensive revolution in baseball. In the 1920s batting averages, home runs, and runs scored soared to new heights. Ruth was also to a large extent responsible for manning the great Yankee dynasty of the 1920s and early 1930s. Between 1921 and 1932 the Yankees won seven pennants and four World Series.

In the 1920s, a decade that produced a galaxy of sports celebrities such as Red Grange in gridiron football and Jack Dempsey in prizefighting, no figure from the world of sport exceeded the public appeal of Ruth. “He has become a national curiosity,” reported The New York Times as early as 1920, “and the sightseeing Pilgrims who daily flock into Manhattan are as anxious to rest eyes on him as they are to see the Woolworth Building.” Each morning men and boys across the United States unfolded their newspapers to see if Ruth had hit yet another home run. Notorious for his enormous appetites for all things of the flesh, Ruth seemed to represent a new era in American history, a time when men and women were freer than they had been in the past to enjoy themselves. He embodied a new model of success. In an increasingly complex world of assembly lines and bureaucracies, Ruth, like other celebrities of the day, leapt to fame and fortune by his sheer natural talents and personal charisma rather than by hard work and self-control. The very words “Ruth” and “Ruthian” entered the American lexicon as benchmarks to describe outstanding performers and performances in all fields of human endeavour. As with no other sports figure in American history except perhaps Muhammad Ali, Ruth continued long after his playing career ended to occupy a towering place in America’s imagination.