Daniel Burnham

Daniel Burnham

United States of America

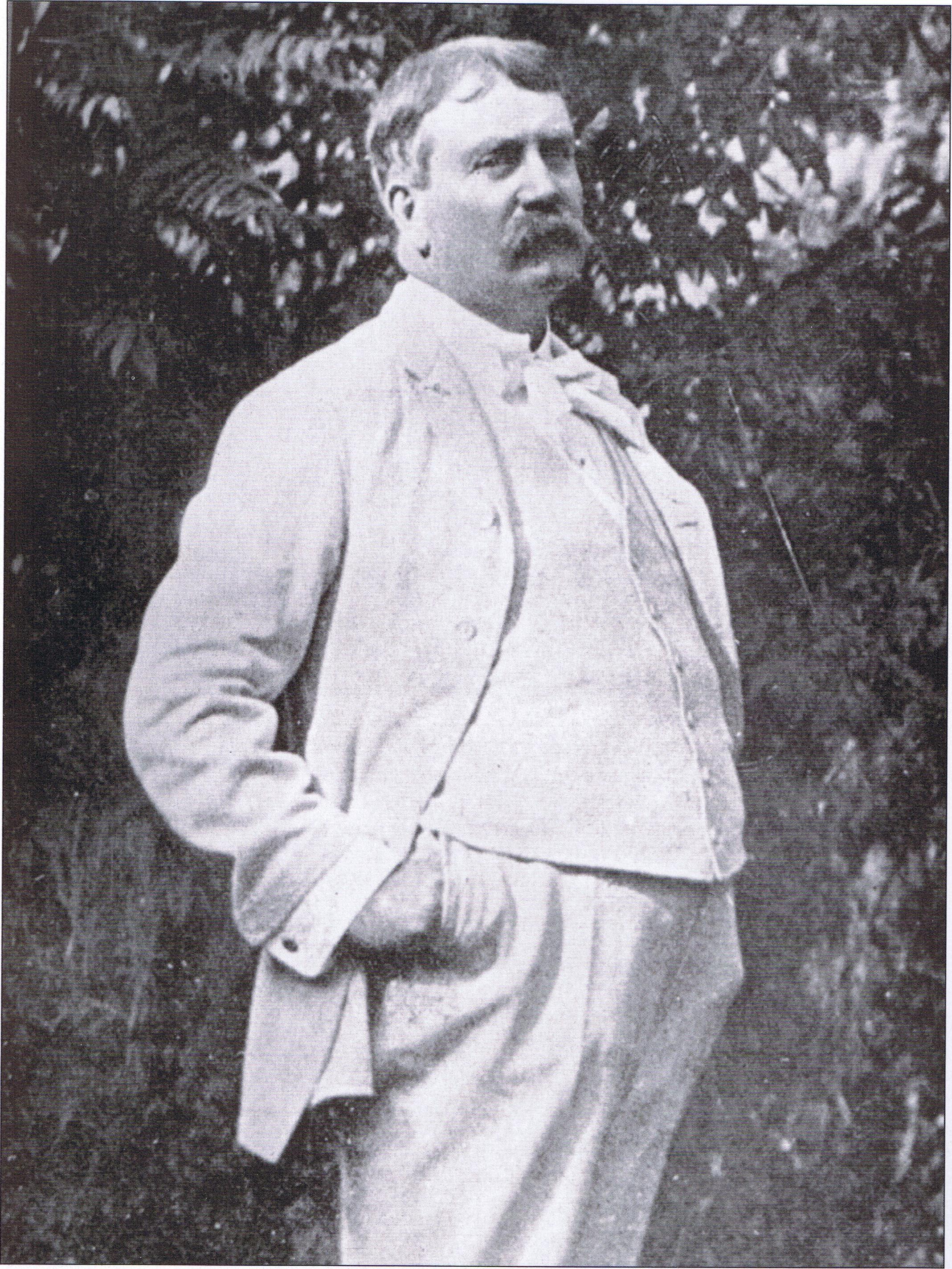

United States of AmericaDaniel Burnham, in full Daniel Hudson Burnham, (born September 4, 1846, Henderson, New York, U.S.—died June 1, 1912, Heidelberg, Germany), American architect and urban planner whose impact on the American city was substantial. He was instrumental in the development of the skyscraper and was noted for his highly successful management of the World’s Columbian Exposition of 1893 and his ideas about urban planning.

Burnham was the sixth of seven children and the youngest son. His parents were members of the Church of the New Jerusalem (now New Church), or Swedenborgians, a maverick Christian religious sect named for Emanuel Swedenborg, a Swedish scientist and mystic who disagreed with church hierarchy and stressed being of service to others.

Burnham and his family moved to Chicago in January 1855. There he attended Snow’s Swedenborgian Academy and later Central High School, where he was remembered for his leadership and artistic ability. In 1863, after he had graduated, his parents sent him to the newly incorporated New-Church Theological School in Waltham, Massachusetts, for further study. He prepared for college with a Swedenborgian tutor, the Reverend Tilly Brown Hayward. Through Hayward, Burnham met the architect and writer W.P.P. Longfellow, who encouraged Burnham’s interest in architecture. When it came time to take his college entrance exams at Harvard and Yale, he failed both because he was “not able to write a word,” as he later recalled. Years later both universities would award him honorary degrees.

Returning to Chicago, Burnham became a draftsman for the famed civil engineer and architect William Le Baron Jenney. He wrote to his mother in 1868 that he would become “the greatest architect in the city and country.” Nevertheless, ambitious, young, and restless, he quit his job with Jenney in order to seek his fortune in Nevada, where he tried mining and also ran for the state senate. Unsuccessful in both attempts, he returned to Chicago in 1870 ready to begin an architectural career in earnest.

In 1872 Burnham joined the office of Carter, Drake & Wight, where he met John Wellborn Root, a talented architect and the office foreman. Burnham, eager to start his own firm, persuaded Root to become his partner a year later. Root was primarily responsible for design while Burnham planned the layout of their building interiors and organized the business. As best friends and professional colleagues, they worked closely together. Of their business relationship, their one-time boss Peter Wight recalled in a 1912 address before the Illinois chapter of the American Institute of Architects: Burnham had a great faculty of impressing his clients with the firm’s ability to solve any problem that came to it. He would make rapid sketches, which Root afterward elaborated with the greatest care. He inspired confidence in all who came within the range of his positive and powerful personality. Root had the ability to carry to success anything that Burnham offered to do.

Burnham & Root became one of the preeminent firms in the history of American architecture. It was known for its size and wide range of projects.

Their talent was evident from the start of their partnership. One of their first commissions, a house for the Union Stockyards magnate John B. Sherman in 1874, caught the discerning eye of their contemporary and rival Louis Sullivan, who recalled its fine lines and proportions in his autobiography.

Two events triggered a period of extraordinary growth in Chicago: the end of the Civil War and the Chicago fire of 1871. Burnham, always thinking big, was quick to recognize the needs of commercial clients. A series of bold solutions to some of the challenges of building higher structures provided examples for others to follow and led Burnham & Root to the forefront of their profession. As an example, for the 10-story Montauk Block (1882–83)—perhaps the first building to be labeled a “skyscraper”—Burnham & Root devised a new kind of foundation footing. This footing, consisting of a broad slab of concrete reinforced with iron rails, allowed the Montauk, and future taller, heavier buildings, to be built in Chicago’s unstable soil. Burnham & Root also extended the typical Chicago construction time frame by continuing to build throughout the winter months. They used a tentlike structure over the site and placed heaters inside. Additionally, the Montauk was noteworthy for its fireproofing system, which employed a hollow tile subfloor and tiles to encase both beams and columns, and was hailed as one of the first truly fireproof buildings. The Montauk Block created a new urban scale for commercial structures, while its form and plain surfaces reflected an aesthetic based on functionality, a hallmark of the new commercial architecture.

Among their other notable early works are the Rookery (completed 1886), the second Rand McNally Building (completed 1890, demolished 1911), the Monadnock Building (completed 1891), and the Masonic Temple (completed 1892). Finished a year after William Le Baron Jenney’s Home Insurance Building (completed 1885), which was the first building to use structural steel members for partial support, the Rookery used both a masonry load-bearing wall and a skeleton frame (a grid of vertical steel columns and horizontal steel beams) in its construction. But it is the smaller Rand McNally Building that is credited as the first steel-frame building. Burnham & Root’s 16-story Monadnock Building reached the tallest practical height using traditional construction techniques. At 21 stories high, Burnham & Root’s Masonic Temple with its great atrium would be a wonder: the tallest office building in the world in terms of occupied floors. In their 18-year partnership, Burnham and Root built nearly 300 structures—among them railroad stations, warehouses, office buildings, residences, armories, schools, clubs, and churches.

At a time when architecture was still emerging as a profession, Burnham organized his office for maximum efficiency and created a model for future architectural firms. The firm’s clients were ushered into a handsome paneled office with velvet curtains, a library of architectural drawing books, and a small copy of the Venus de Milo perched on the mantle over the fireplace. The tradesmen with whom they worked were scheduled to meet with the firm only on designated days. The office floorplan, which was published as a model for the profession, even had a gym.

The World’s Columbian Exposition of 1893

Burnham’s extraordinary leadership skills were made manifest when he became the director of works at the World’s Columbian Exposition of 1893. Burnham & Root were first named consulting architects, but Burnham resigned that position to become head of construction. When Root died suddenly in January 1891, Burnham assumed responsibility for overseeing and completing construction for some 150 buildings on more than 600 acres (240 hectares) of land.

In little more than two years, working with America’s most noted architects and designers, Burnham developed America’s most spectacular world’s fair of the 19th century. He led a workforce that reached 10,000 men, reviewed guidelines for the many state buildings, and oversaw the fair’s infrastructure, including transportation, sewage, and clean water delivery systems. Nicknamed the “White City,” the fair’s grand Neoclassical buildings were planned as a cohesive whole in a landscaped setting; they made a lasting impression on millions of visitors. Often noted as the inspiration for the City Beautiful movement, the fair proved to be a turning point both for Burnham and for the development of the modern American city.

D.H. Burnham and Company

When he was able to return to his architecture practice, Burnham reorganized it as D.H. Burnham and Company. Aesthetically, he embraced a traditional Neoclassical vocabulary utilized at the Court of Honor at the fair and exemplified by his friend the architect Charles F. McKim of McKim, Mead & White. Burnham’s firm completed designs for more than 200 buildings in the next 20 years, including many that are significant in American architectural history.

Among these is counted the Reliance Building (1895), by Burnham’s chief designer Charles Atwood, considered a landmark in the development of the tall office building, because the slim glass and steel tower presaged Modernist skyscrapers. Burnham continued to think big. At 500,000 square feet (45,000 square metres), his Ellicott Square Building (completed 1896) in Buffalo, New York, occupies a full city block and was the largest building of its time. Other notable Burnham structures are the famous Flatiron Building (completed 1902) in New York City; the Field Museum (completed 1920) in Chicago; the Frick and Oliver buildings (completed 1902 and 1910, respectively) in Pittsburgh; a series of department stores such as Wanamaker’s (1909) in Philadelphia, Selfridges (completed 1909) in London, Marshall Field & Company (completed 1907) in Chicago, and Gimbels (completed 1912) in Manhattan; and Union Station (completed 1907) in Washington, D.C.

Urban planner

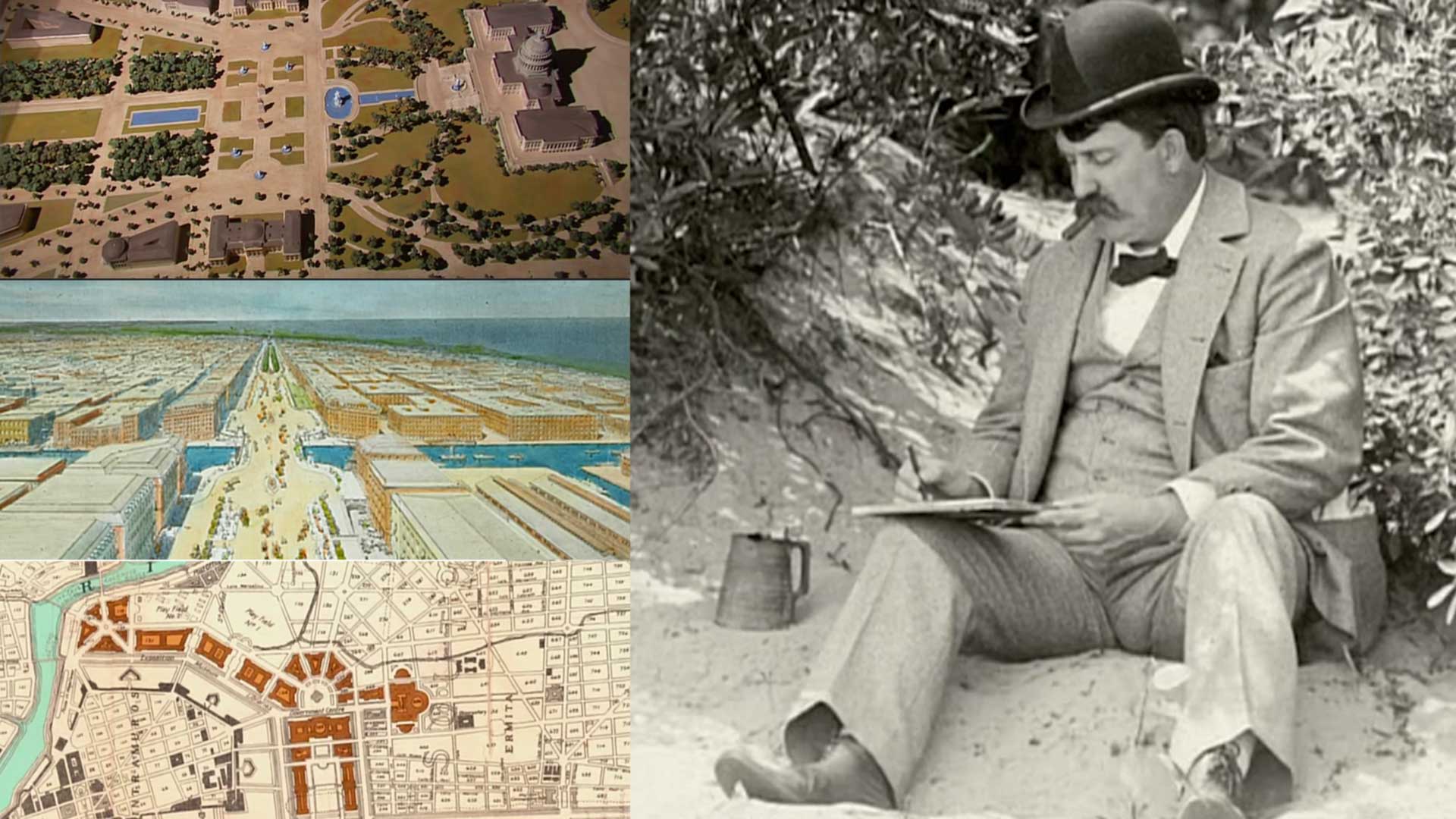

His work on the fair had developed in Burnham a keen interest in parks and city planning. He believed that an improved urban environment could provide a positive transformative experience for its inhabitants. Burnham’s first opportunity to put his ideas in action (he had set forth his ideas to no avail earlier in Chicago) came in 1901, when he became the de facto chairman of the Senate Park Commission, also called the McMillan Commission (for Michigan’s U.S. Sen. James McMillan, who was chairman of the Senate Committee on the District of Columbia). Burnham invited his friend McKim and Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr. (son of the famous landscape architect with whom Burnham had worked on the fair), to join him in re-envisioning and enlarging Pierre-Charles L’Enfant’s original 1791 plan: they undertook much of the actual work. Under Burnham’s leadership and based on precedents in Paris and especially Rome, the team envisioned a grand, ordered national capital to reflect America’s status as an emerging world power. Their plan for the capital city included a comprehensive park system and redefined the National Mall and surrounding area. Burnham further conceived of Union Station, the railway station, as a formal public gateway to the city’s monumental core and as a feature integral to the city plan. Upon publication the McMillan Plan received widespread attention and approval.

Fueled by the Progressive era’s interest in municipal improvement, other cities requested Burnham’s planning services. In 1902–03 Burnham, with architects Arnold W. Brunner and John M. Carrère, prepared for the city of Cleveland a “Group Plan” for a new downtown civic centre of Beaux Arts buildings formally arranged around a rectangular park. In 1905, under the auspices of leading private citizens organized as the Association for the Improvement and Adornment of San Francisco, Burnham devised for San Francisco a far more comprehensive plan. However, in the aftermath of the 1906 earthquake, this plan was not implemented. In the meantime, Burnham’s architectural practice continued to flourish. So famous had he become as a city planner that, when the Philippines were ceded to the United States after the Spanish American War, Burnham was asked by the federal government to create a “Beautification Plan” for Manila and to design an entirely new summer capital, Baguio, in the Luzon highlands. He responded by recommending the preservation of Manila’s old walled Spanish city, and in both cities he utilized familiar City Beautiful components: a system of parks, a network of diagonal roadways for traffic efficiency, and a civic centre complex, formally arranged as the heart of the community.

Burnham thus brought a lifetime of experience to his masterwork, the 1909 Plan of Chicago, written with his young associate, Edward Bennett. Published by and written for the Commercial Club of Chicago, a private group of civic-minded business leaders who worked closely with Burnham on the report, the book is considered a landmark in urban planning history. It recognized the city in its context, not as an isolated collection of buildings but as an organic whole interconnected with and interrelated to its region. It encompassed a 60-mile radius that included three states and Lake Michigan. Visionary yet detailed, the plan boldly confronted the complexities of the modern industrial city and argued that solutions could be found that would improve infrastructure, relieve traffic congestion, provide open space, and enhance the physical environment in lasting, meaningful ways for its inhabitants. Reserving the lakefront as public space was one of Burnham’s major concerns and one of the plan’s most notable accomplishments.

Burnham and the Commercial Club members realized the importance of marketing to gain support for their ideas. To this end, the Plan of Chicago was handsomely printed and included evocative drawings of what Chicago could look like interspersed with photographs and detailed maps and graphs. It was released to the public on July 4, 1909. Civic, cultural, and educational leaders were consulted during its preparation, and a traveling exhibition of the drawings created for the project was prepared for display both in the United States and abroad. The Plan of Chicago draws on European precedents, especially on Baron Haussmann’s Paris, with its broad diagonal streets, as well as on Beaux Arts concepts of balance, axiality, and symmetry. Although the Plan of Chicago received great acclaim initially, it did not take into account the enormous impact of the automobile. Some critics noted even at the time that it ignored housing and other pressing urban social issues. Burnham’s unpublished draft of the Plan, however, does include a remarkable social agenda. Others since have argued that Burnham’s plan represents an elitist viewpoint with an emphasis on social control and order; it is, these critics argue, too comprehensive to be fully realized and too monumental to be humane. Nonetheless, the Plan of Chicago has inspired generations of Chicagoans and others to work toward the ideal of a beautiful, efficient city.

Burnham did not see any aspect of his Chicago plan realized. Already diagnosed with diabetes, he died on June 1, 1912, of food poisoning while on a trip abroad and is buried in Graceland Cemetery in Chicago.

Burnham himself published little. His major work is the 1909 Plan of Chicago, coauthored with Edward H. Bennett, that outlines specific recommendations but also includes more general ideas about urban planning. Burnham also wrote or cowrote reports for his other urban planning projects: Washington, D.C., The Improvement of the Park System of the District of Columbia (1902), known commonly as the McMillan report; Cleveland, The Group Plan of Public Buildings at Cleveland (1903); San Francisco, Report on a Plan for San Francisco (1905); and Manila in the Philippines, Report on Proposed Improvements at Manila (1906). As Director of Works for the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition, Burnham is the author of the two-volume The Final Official Report of the Director of Works of the World’s Columbian Exposition. He wrote many letters, which can be found in the Burnham papers at the Art Institute of Chicago. They reveal a busy man who cared deeply about his friends and family, saw to details, and believed in the power of beauty.

Legacy

Despite the criticisms of his Plan of Chicago, Burnham has a vast legacy that endures. In Root he chose a partner who complemented him perfectly, and together they built one of the largest and most successful firms in the country. In the process of doing so, Burnham created organizational systems that transformed the practice of architecture in the modern age. He was among the earliest developers of the skyscraper, and his vision for the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition helped inspire the City Beautiful movement, and—before the profession of urban planning existed—he created plans for major cities in the United States and abroad. Burnham was a leader in his profession who believed that the architect had a professional responsibility toward the larger community of which he was a part.