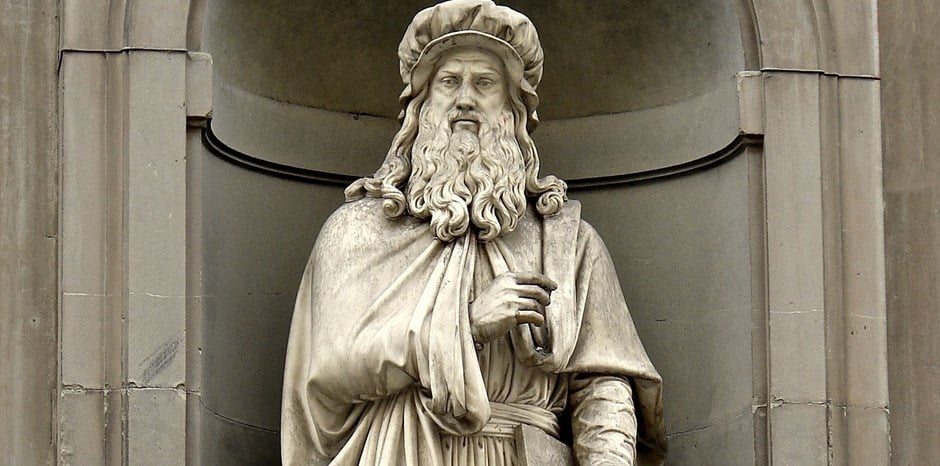

Leonardo da Vinci

Leonardo da Vinci

Duchy of Milan

Duchy of Milan Kingdom of France

Kingdom of France Republic of Florence

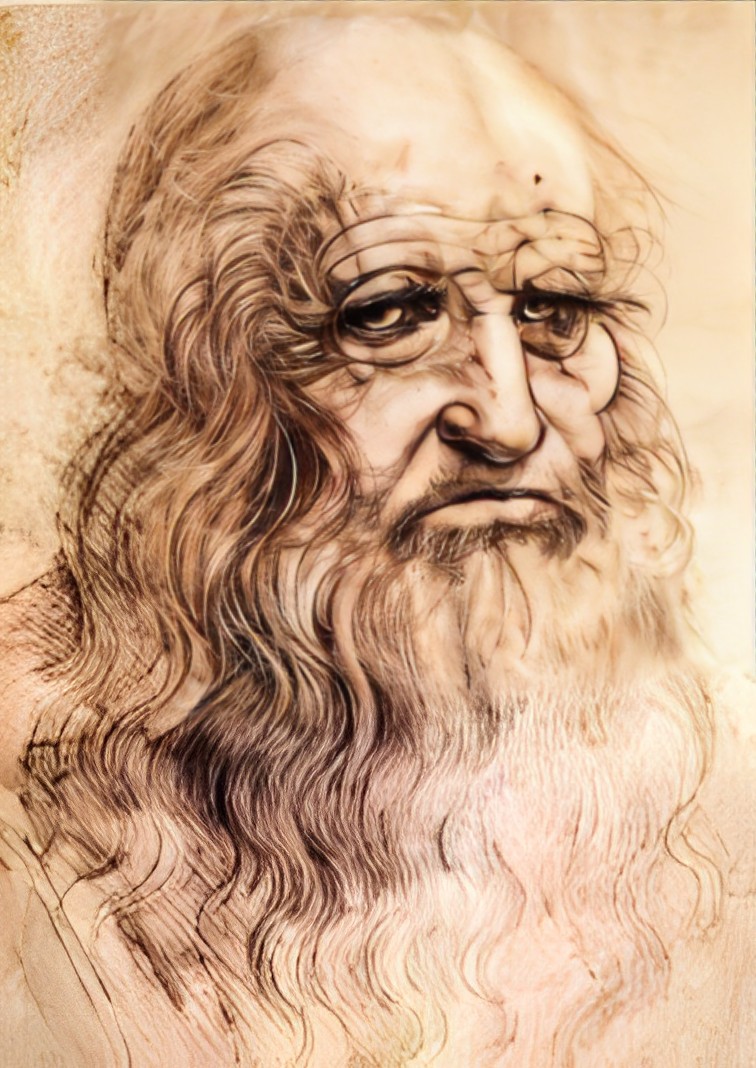

Republic of FlorenceLeonardo da Vinci, (Italian: “Leonardo from Vinci”) (born April 15, 1452, Anchiano, near Vinci, Republic of Florence [Italy]—died May 2, 1519, Cloux [now Clos-Lucé], France), Italian painter, draftsman, sculptor, architect, and engineer whose skill and intelligence, perhaps more than that of any other figure, epitomized the Renaissance humanist ideal. His Last Supper (1495–98) and Mona Lisa (c. 1503–19) are among the most widely popular and influential paintings of the Renaissance. His notebooks reveal a spirit of scientific inquiry and a mechanical inventiveness that were centuries ahead of their time.

The unique fame that Leonardo enjoyed in his lifetime and that, filtered by historical criticism, has remained undimmed to the present day rests largely on his unlimited desire for knowledge, which guided all his thinking and behaviour. An artist by disposition and endowment, he considered his eyes to be his main avenue to knowledge; to Leonardo, sight was man’s highest sense because it alone conveyed the facts of experience immediately, correctly, and with certainty. Hence, every phenomenon perceived became an object of knowledge, and saper vedere (“knowing how to see”) became the great theme of his studies. He applied his creativity to every realm in which graphic representation is used: he was a painter, sculptor, architect, and engineer. But he went even beyond that. He used his superb intellect, unusual powers of observation, and mastery of the art of drawing to study nature itself, a line of inquiry that allowed his dual pursuits of art and science to flourish.

Leonardo’s parents were unmarried at the time of his birth. His father, Ser Piero, was a Florentine notary and landlord, and his mother, Caterina, was a young peasant woman who shortly thereafter married an artisan. Leonardo grew up on his father’s family’s estate, where he was treated as a “legitimate” son and received the usual elementary education of that day: reading, writing, and arithmetic. Leonardo did not seriously study Latin, the key language of traditional learning, until much later, when he acquired a working knowledge of it on his own. He also did not apply himself to higher mathematics—advanced geometry and arithmetic—until he was 30 years old, when he began to study it with diligent tenacity.

Leonardo’s artistic inclinations must have appeared early. When he was about 15, his father, who enjoyed a high reputation in the Florence community, apprenticed him to artist Andrea del Verrocchio. In Verrocchio’s renowned workshop Leonardo received a multifaceted training that included painting and sculpture as well as the technical-mechanical arts. He also worked in the next-door workshop of artist Antonio Pollaiuolo. In 1472 Leonardo was accepted into the painters’ guild of Florence, but he remained in his teacher’s workshop for five more years, after which time he worked independently in Florence until 1481. There are a great many superb extant pen and pencil drawings from this period, including many technical sketches—for example, pumps, military weapons, mechanical apparatus—that offer evidence of Leonardo’s interest in and knowledge of technical matters even at the outset of his career.

First Milanese period (1482–99)

In 1482 Leonardo moved to Milan to work in the service of the city’s duke—a surprising step when one realizes that the 30-year-old artist had just received his first substantial commissions from his native city of Florence: the unfinished panel painting Adoration of the Magi for the monastery of San Donato a Scopeto and an altar painting for the St. Bernard Chapel in the Palazzo della Signoria, which was never begun. That he gave up both projects seems to indicate that he had deeper reasons for leaving Florence. It may have been that the rather sophisticated spirit of Neoplatonism prevailing in the Florence of the Medici went against the grain of Leonardo’s experience-oriented mind and that the more strict, academic atmosphere of Milan attracted him. Moreover, he was no doubt enticed by Duke Ludovico Sforza’s brilliant court and the meaningful projects awaiting him there.

Leonardo spent 17 years in Milan, until Ludovico’s fall from power in 1499. He was listed in the register of the royal household as pictor et ingeniarius ducalis (“painter and engineer of the duke”). Leonardo’s gracious but reserved personality and elegant bearing were well-received in court circles. Highly esteemed, he was constantly kept busy as a painter and sculptor and as a designer of court festivals. He was also frequently consulted as a technical adviser in the fields of architecture, fortifications, and military matters, and he served as a hydraulic and mechanical engineer. As he would throughout his life, Leonardo set boundless goals for himself; if one traces the outlines of his work for this period, or for his life as a whole, one is tempted to call it a grandiose “unfinished symphony.”

As a painter, Leonardo completed six works in the 17 years in Milan. (According to contemporary sources, Leonardo was commissioned to create three more pictures, but these works have since disappeared or were never done.) From about 1483 to 1486, he worked on the altar painting The Virgin of the Rocks, a project that led to 10 years of litigation between the Confraternity of the Immaculate Conception, which commissioned it, and Leonardo; for uncertain purposes, this legal dispute led Leonardo to create another version of the work in about 1508. During this first Milanese period he also made one of his most famous works, the monumental wall painting Last Supper (1495–98) in the refectory of the monastery of Santa Maria delle Grazie (for more analysis of this work, see below Last Supper). Also of note is the decorative ceiling painting (1498) he made for the Sala delle Asse in the Milan Castello Sforzesco.

During this period Leonardo worked on a grandiose sculptural project that seems to have been the real reason he was invited to Milan: a monumental equestrian statue in bronze to be erected in honour of Francesco Sforza, the founder of the Sforza dynasty. Leonardo devoted 12 years—with interruptions—to this task. In 1493 the clay model of the horse was put on public display on the occasion of the marriage of Emperor Maximilian to Bianca Maria Sforza, and preparations were made to cast the colossal figure, which was to be 16 feet (5 metres) high. But, because of the imminent danger of war, the metal, ready to be poured, was used to make cannons instead, causing the project to come to a halt. Ludovico’s fall in 1499 sealed the fate of this abortive undertaking, which was perhaps the grandest concept of a monument in the 15th century. The ensuing war left the clay model a heap of ruins.

As a master artist, Leonardo maintained an extensive workshop in Milan, employing apprentices and students. Among Leonardo’s pupils at this time were Giovanni Antonio Boltraffio, Ambrogio de Predis, Bernardino de’ Conti, Francesco Napoletano, Andrea Solari, Marco d’Oggiono, and Salai. The role of most of these associates is unclear, leading to the question of Leonardo’s so-called apocryphal works, on which the master collaborated with his assistants. Scholars have been unable to agree in their attributions of these works.

Second Florentine period (1500–08) of Leonardo da Vinci

In December 1499 or, at the latest, January 1500—shortly after the victorious entry of the French into Milan—Leonardo left that city in the company of mathematician Lucas Pacioli. After visiting Mantua in February 1500, in March he proceeded to Venice, where the Signoria (governing council) sought his advice on how to ward off a threatened Turkish incursion in Friuli. Leonardo recommended that they prepare to flood the menaced region. From Venice he returned to Florence, where, after a long absence, he was received with acclaim and honoured as a renowned native son. In that same year he was appointed an architectural expert on a committee investigating damages to the foundation and structure of the church of San Francesco al Monte. A guest of the Servite order in the cloister of Santissima Annunziata, Leonardo seems to have been concentrating more on mathematical studies than painting, or so Isabella d’Este, who sought in vain to obtain a painting done by him, was informed by Fra Pietro Nuvolaria, her representative in Florence.

Perhaps because of his omnivorous appetite for life, Leonardo left Florence in the summer of 1502 to enter the service of Cesare Borgia as “senior military architect and general engineer.” Borgia, the notorious son of Pope Alexander VI, had, as commander in chief of the papal army, sought with unexampled ruthlessness to gain control of the Papal States of Romagna and the Marches. When he enlisted the services of Leonardo, he was at the peak of his power and, at age 27, was undoubtedly the most compelling and most feared person of his time. Leonardo, twice his age, must have been fascinated by his personality. For 10 months Leonardo traveled across the condottiere’s territories and surveyed them. In the course of his activity, he sketched some of the city plans and topographical maps, creating early examples of aspects of modern cartography. At the court of Cesare Borgia, Leonardo also met Niccolò Machiavelli, who was temporarily stationed there as a political observer for the city of Florence.

In the spring of 1503 Leonardo returned to Florence to make an expert survey of a project that attempted to divert the Arno River behind Pisa so that the city, then under siege by the Florentines, would be deprived of access to the sea. The plan proved unworkable, but Leonardo’s activity led him to consider a plan, first advanced in the 13th century, to build a large canal that would bypass the unnavigable stretch of the Arno and connect Florence by water with the sea. Leonardo developed his ideas in a series of studies; using his own panoramic views of the riverbank, which can be seen as landscape sketches of great artistic charm, and using exact measurements of the terrain, he produced a map in which the route of the canal (with its transit through the mountain pass of Serravalle) was shown. The project, considered time and again in subsequent centuries, was never carried out, but centuries later the express highway from Florence to the sea was built over the exact route Leonardo chose for his canal.

Also in 1503 Leonardo received a prized commission to paint a mural for the council hall in Florence’s Palazzo Vecchio; a historical scene of monumental proportions (at 23 × 56 feet [7 × 17 metres], it would have been twice as large as the Last Supper). For three years he worked on this Battle of Anghiari; like its intended complementary painting, Michelangelo’s Battle of Cascina, it remained unfinished. During these same years Leonardo painted the Mona Lisa (c. 1503–19). (For more analysis of the work, see below The Mona Lisa and other works.)

The second Florentine period was also a time of intensive scientific study. Leonardo did dissections in the hospital of Santa Maria Nuova and broadened his anatomical work into a comprehensive study of the structure and function of the human organism. He made systematic observations of the flight of birds, about which he planned a treatise. Even his hydrological studies, “on the nature and movement of water,” broadened into research on the physical properties of water, especially the laws of currents, which he compared with those pertaining to air. These were also set down in his own collection of data, contained in the so-called Codex Hammer (formerly known as the Leicester Codex, now in the property of software entrepreneur Bill Gates in Seattle, Washington, U.S.).

Second Milanese period (1508–13)

In May 1506 Charles d’Amboise, the French governor in Milan, asked the Signoria in Florence if Leonardo could travel to Milan. The Signoria let Leonardo go, and the monumental Battle of Anghiari remained unfinished. Unsuccessful technical experiments with paints seem to have impelled Leonardo to stop working on the mural; one cannot otherwise explain his abandonment of this great work. In the winter of 1507–08 Leonardo went to Florence, where he helped the sculptor Giovanni Francesco Rustici execute his bronze statues for the Florence Baptistery, after which time he settled in Milan.

Honoured and admired by his generous patrons in Milan, Charles d’Amboise and King Louis XII, Leonardo enjoyed his duties, which were limited largely to advice in architectural matters. Tangible evidence of such work exists in plans for a palace-villa for Charles, and it is believed that he made some sketches for an oratory for the church of Santa Maria alla Fontana, which Charles funded. Leonardo also looked into an old project revived by the French governor: the Adda River that would link Milan with Lake Como by water.

During this second period in Milan, Leonardo created very little as a painter. Again Leonardo gathered pupils around him. Of his older disciples, Bernardino de’ Conti and Salai were again in his studio; new students came, among them Cesare da Sesto, Giampetrino, Bernardino Luini, and the young nobleman Francesco Melzi, Leonardo’s most faithful friend and companion until the artist’s death.

An important commission came Leonardo’s way during this time. Gian Giacomo Trivulzio had returned victoriously to Milan as marshal of the French army and as a bitter foe of Ludovico Sforza. He commissioned Leonardo to sculpt his tomb, which was to take the form of an equestrian statue and be placed in the mortuary chapel donated by Trivulzio to the church of San Nazaro Maggiore. After years of preparatory work on the monument, for which a number of significant sketches have survived, the marshal himself gave up the plan in favour of a more modest one. This was the second aborted project Leonardo faced as a sculptor.

Leonardo’s scientific activity flourished during this period. His studies in anatomy achieved a new dimension in his collaboration with Marcantonio della Torre, a famous anatomist from Pavia. Leonardo outlined a plan for an overall work that would include not only exact, detailed reproductions of the human body and its organs but would also include comparative anatomy and the whole field of physiology. He even planned to finish his anatomical manuscript in the winter of 1510–11. Beyond that, his manuscripts are replete with mathematical, optical, mechanical, geological, and botanical studies. These investigations became increasingly driven by a central idea: the conviction that force and motion as basic mechanical functions produce all outward forms in organic and inorganic nature and give them their shape. Furthermore, he believed that these functioning forces operate in accordance with orderly, harmonious laws.

Last years (1513–19) of Leonardo da Vinci

In 1513 political events—the temporary expulsion of the French from Milan—caused the now 60-year-old Leonardo to move again. At the end of the year, he went to Rome, accompanied by his pupils Melzi and Salai as well as by two studio assistants, hoping to find employment there through his patron Giuliano de’ Medici, brother of the new pope, Leo X. Giuliano gave him a suite of rooms in his residence, the Belvedere, in the Vatican. He also gave Leonardo a considerable monthly stipend, but no large commissions followed. For three years Leonardo remained in Rome at a time of great artistic activity: Donato Bramante was building St. Peter’s, Raphael was painting the last rooms of the pope’s new apartments, Michelangelo was struggling to complete the tomb of Pope Julius II, and many younger artists, such as Timoteo Viti and Sodoma, were also active. Drafts of embittered letters betray the disappointment of the aging master, who kept a low profile while he worked in his studio on mathematical studies and technical experiments or surveyed ancient monuments as he strolled through the city. Leonardo seems to have spent time with Bramante, but the latter died in 1514, and there is no record of Leonardo’s relations with any other artists in Rome. A magnificently executed map of the Pontine Marshes suggests that Leonardo was at least a consultant for a reclamation project that Giuliano de’ Medici ordered in 1514. He also made sketches for a spacious residence to be built in Florence for the Medici, who had returned to power there in 1512. However, the structure was never built.

Perhaps stifled by this scene, at age 65 Leonardo accepted the invitation of the young King Francis I to enter his service in France. At the end of 1516 he left Italy forever, together with Melzi, his most devoted pupil. Leonardo spent the last three years of his life in the small residence of Cloux (later called Clos-Lucé), near the king’s summer palace at Amboise on the Loire. He proudly bore the title Premier peintre, architecte et méchanicien du Roi (“First painter, architect, and engineer to the King”). Leonardo still made sketches for court festivals, but the king treated him in every respect as an honoured guest and allowed him freedom of action. Decades later, Francis I talked with the sculptor Benvenuto Cellini about Leonardo in terms of the utmost admiration and esteem. For the king, Leonardo drew up plans for the palace and garden of Romorantin, which was destined to be the widow’s residence of the Queen Mother. But the carefully worked-out project, combining the best features of Italian-French traditions in palace and landscape architecture, had to be halted because the region was threatened with malaria.

Leonardo did little painting while in France, spending most of his time arranging and editing his scientific studies, his treatise on painting, and a few pages of his anatomy treatise. In the so-called Visions of the End of the World series (c. 1517–18), which includes the drawings A Deluge, he depicted with overpowering imagination the primal forces that rule nature, while also perhaps betraying his growing pessimism.

Leonardo died at Cloux and was buried in the palace church of Saint-Florentin. The church was devastated during the French Revolution and completely torn down at the beginning of the 19th century; his grave can no longer be located. Melzi was heir to Leonardo’s artistic and scientific estate.

Painting and drawing

Leonardo’s total output in painting is really rather small; only 17 of the paintings that have survived can be definitely attributed to him, and several of them are unfinished. Two of his most important works—the Battle of Anghiari and the Leda, neither of them completed—have survived only in copies. Yet these few creations have established the unique fame of a man whom Giorgio Vasari, in his seminal Lives of the Most Eminent Italian Architects, Painters and Sculptors (1550, 2nd ed., 1568), described as the founder of the High Renaissance. Leonardo’s works, unaffected by the vicissitudes of aesthetic doctrines in subsequent centuries, have stood out in all subsequent periods and all countries as consummate masterpieces of painting.

The many testimonials to Leonardo, ranging from Vasari to Peter Paul Rubens to Johann Wolfgang von Goethe to Eugène Delacroix, praise in particular the artist’s gift for expression—his ability to move beyond technique and narrative to convey an underlying sense of emotion. The artist’s remarkable talent, especially his keenness of observation and creative imagination, was already revealed in the angel he contributed to Verrocchio’s Baptism of Christ (c. 1472–75): Leonardo endowed the angel with natural movement, presented it with a relaxed demeanour, and gave it an enigmatic glance that both acknowledges its surroundings while remaining inwardly directed. In Leonardo’s landscape segment in the same picture, he also found a new expression for what he called “nature experienced”: he reproduced the background forms in a hazy fashion as if through a veil of mist.

In the The Benois Madonna (1478–80) Leonardo succeeded in giving a traditional type of picture a new, unusually charming, and expressive mood by showing the child Jesus reaching, in a sweet and tender manner, for the flower in Mary’s hand. In the portrait Ginevra de’ Benci (c. 1474/78), Leonardo opened new paths for portrait painting with his singular linking of nearness and distance and his brilliant rendering of light and texture. He presented the emaciated body of his St. Jerome (unfinished; c. 1482) in a sobering light, imbuing it with a realism that stemmed from his keen knowledge of anatomy; Leonardo’s mastery of gesture and facial expression gave his Jerome an unrivalled expression of transfigured sorrow.

The interplay of masterful technique and affective gesture—“physical and spiritual motion,” in Leonardo’s words—is also the chief concern of his first large creation containing many figures, Adoration of the Magi (c. 1482). Never finished, the painting nonetheless affords rich insight into the master’s subtle methods. The various aspects of the scene are built up from the base with very delicate paper-thin layers of paint in sfumato (the smooth transition from light to shadow) relief. The main treatment of the Virgin and Child group and the secondary treatment of the surrounding groups are clearly set apart with a masterful sense of composition—the pyramid of the Virgin Mary and Magi is demarcated from the arc of the adoring followers. Yet thematically they are closely interconnected: the bearing and expression of the figures—most striking in the group of praying shepherds—depict many levels of profound amazement.

The Virgin of the Rocks in its first version (1483–86) is the work that reveals Leonardo’s painting at its purest. It depicts the apocryphal legend of the meeting in the wilderness between the young John the Baptist and Jesus returning home from Egypt. The secret of the picture’s effect lies in Leonardo’s use of every means at his disposal to emphasize the visionary nature of the scene: the soft colour tones (through sfumato), the dim light of the cave from which the figures emerge bathed in light, their quiet attitude, the meaningful gesture with which the angel (the only figure facing the viewer) points to John as the intercessor between the Son of God and humanity—all this combines, in a patterned and formal way, to create a moving and highly expressive work of art.

Last Supper of Leonardo da Vinci

Leonardo’s Last Supper (1495–98) is among the most famous paintings in the world. In its monumental simplicity, the composition of the scene is masterful; the power of its effect comes from the striking contrast in the attitudes of the 12 disciples as counterposed to Christ. Leonardo portrayed a moment of high tension when, surrounded by the Apostles as they share Passover, Jesus says, “One of you will betray me.” All the Apostles—as human beings who do not understand what is about to occur—are agitated, whereas Christ alone, conscious of his divine mission, sits in lonely, transfigured serenity. Only one other being shares the secret knowledge: Judas, who is both part of and yet excluded from the movement of his companions. In this isolation he becomes the second lonely figure—the guilty one—of the company.

In the profound conception of his theme, in the perfect yet seemingly simple arrangement of the individuals, in the temperaments of the Apostles highlighted by gesture, facial expressions, and poses, in the drama and at the same time the sublimity of the treatment, Leonardo attained a height of expression that has remained a model of its kind. Countless painters in succeeding generations, among them great masters such as Rubens and Rembrandt, marveled at Leonardo’s composition and were influenced by it and by the painting’s narrative quality. The work also inspired some of Goethe’s finest pages of descriptive prose. It has become widely known through countless reproductions and prints, the most important being that produced by Raffaello Morghen in 1800. Thus, Last Supper has become part of humanity’s common heritage and remains today one of the world’s outstanding paintings.

Technical deficiencies in the execution of the work have not lessened its fame. Leonardo was uncertain about the technique he should use. He bypassed traditional fresco painting, which, because it is executed on fresh plaster, demands quick and uninterrupted painting, in favour of another technique he had developed: tempera on a base, which he mixed himself, on the stone wall. This procedure proved unsuccessful, inasmuch as the base soon began to loosen from the wall. Damage appeared by the beginning of the 16th century, and deterioration soon set in. By the middle of the century, the work was called a ruin. Later, inadequate attempts at restoration only aggravated the situation, and not until the most-modern restoration techniques were applied after World War II was the process of decay halted. A major restoration campaign begun in 1980 and completed in 1999 restored the work to brilliance but also revealed that very little of the original paint remains.

Art and science: the notebooks

In the years between 1490 and 1495, the great program of Leonardo the writer (author of treatises) began. During this period, his interest in two fields—the artistic and the scientific—developed and shaped his future work, building toward a kind of creative dualism that sparked his inventiveness in both fields. He gradually gave shape to four main themes that were to occupy him for the rest of his life: a treatise on painting, a treatise on architecture, a book on the elements of mechanics, and a broadly outlined work on human anatomy. His geophysical, botanical, hydrological, and aerological researches also began in this period and constitute parts of the “visible cosmology” that loomed before him as a distant goal. He scorned speculative book knowledge, favouring instead the irrefutable facts gained from experience—from saper vedere.

From this approach came Leonardo’s far-reaching concept of a “science of painting.” Leon Battista Alberti and Piero della Francesca had already offered proof of the mathematical basis of painting in their analysis of the laws of perspective and proportion, thereby buttressing his claim of painting being a science. But Leonardo’s claims went much further: he believed that the painter, doubly endowed with subtle powers of perception and the complete ability to pictorialize them, was the person best qualified to achieve true knowledge, as he could closely observe and then carefully reproduce the world around him. Hence, Leonardo conceived the staggering plan of observing all objects in the visible world, recognizing their form and structure, and pictorially describing them exactly as they are.

It was during his first years in Milan that Leonardo began the earliest of his notebooks. He would first make quick sketches of his observations on loose sheets or on tiny paper pads he kept in his belt; then he would arrange them according to theme and enter them in order in the notebook. Surviving in notebooks from throughout his career are a first collection of material for a painting treatise, a model book of sketches for sacred and profane architecture, a treatise on elementary theory of mechanics, and the first sections of a treatise on the human body.

Leonardo’s notebooks add up to thousands of closely written pages abundantly illustrated with sketches—the most voluminous literary legacy any painter has ever left behind. Of more than 40 codices mentioned—sometimes inaccurately—in contemporary sources, 21 have survived; these in turn sometimes contain notebooks originally separate but now bound so that 32 in all have been preserved. To these should be added several large bundles of documents: an omnibus volume in the Biblioteca Ambrosiana in Milan, called Codex Atlanticus because of its size, was collected by the sculptor Pompeo Leoni at the end of the 16th century; after a roundabout journey, its companion volume fell into the possession of the English crown in the 17th century and was placed in the Royal Library in Windsor Castle. Finally, the Arundel Manuscript in the British Museum in London contains a number of Leonardo’s fascicles on various themes.

One special feature that makes Leonardo’s notes and sketches unusual is his use of mirror writing. Leonardo was left-handed, so mirror writing came easily and naturally to him—although it is uncertain why he chose to do so. While somewhat unusual, his script can be read clearly and without difficulty with the help of a mirror—as his contemporaries testified—and should not be looked on as a secret handwriting. But the fact that Leonardo used mirror writing throughout the notebooks, even in his copies drawn up with painstaking calligraphy, forces one to conclude that, although he constantly addressed an imaginary reader in his writings, he never felt the need to achieve easy communication by using conventional handwriting. His writings must be interpreted as preliminary stages of works destined for eventual publication that Leonardo never got around to completing. In a sentence in the margin of one of his late anatomy sketches, he implores his followers to see that his works are printed.

Another unusual feature in Leonardo’s writings is the relationship between word and picture in the notebooks. Leonardo strove passionately for a language that was clear yet expressive. The vividness and wealth of his vocabulary were the result of intense independent study and represented a significant contribution to the evolution of scientific prose in the Italian vernacular. Despite his articulateness, Leonardo gave absolute precedence to the illustration over the written word in his teaching method. Hence, in his notebooks, the drawing does not illustrate the text; rather, the text serves to explain the picture. In formulating his own principle of graphic representations—which he called dimostrazione (“demonstrations”)—Leonardo’s work was a precursor of modern scientific illustration.

The Mona Lisa and other works of Leonardo da Vinci

In the Florence years between 1500 and 1506, Leonardo began three great works that confirmed and heightened his fame: The Virgin and Child with Saint Anne (c. 1503–19), Mona Lisa (c. 1503–19), and Battle of Anghiari (unfinished; begun 1503). Even before it was completed, The Virgin and Child with Saint Anne won the critical acclaim of the Florentines; the monumental three-dimensional quality of the group and the calculated effects of dynamism and tension in the composition made it a model that inspired Classicists and Mannerists in equal measure.

The Mona Lisa set the standard for all future portraits. The painting presents a woman revealed in the 21st century to likely have been Lisa del Giocondo, the wife of the Florentine merchant Francesco del Giocondo—hence, the alternative title to the work, La Gioconda. The picture presents a half-body portrait of the subject, with a distant landscape visible as a backdrop. Although utilizing a seemingly simple formula for portraiture, the expressive synthesis that Leonardo achieved between sitter and landscape has placed this work in the canon of the most-popular and most-analyzed paintings of all time. The sensuous curves of the woman’s hair and clothing, created through sfumato, are echoed in the undulating valleys and rivers behind her. The sense of overall harmony achieved in the painting—especially apparent in the sitter’s faint smile—reflects Leonardo’s idea of the cosmic link connecting humanity and nature, making this painting an enduring record of Leonardo’s vision and genius. The young Raphael sketched the work in progress, and it served as a model for his Portrait of Maddalena Doni (c. 1506).

Leonardo’s art of expression reached another high point in the unfinished Battle of Anghiari. The preliminary drawings—many of which have been preserved—reveal Leonardo’s lofty conception of the “science of painting”; he put to artistic use the laws of equilibrium that he had probed in his studies of mechanics. The “centre of gravity” in the work lies in the group of flags fought for by all the horsemen. For a moment the intense and expanding movement of the swirl of riders seems frozen. Leonardo’s studies in anatomy and physiology influenced his representation of human and animal bodies, particularly when they are in a state of excitement. He studied and described extensively the baring of teeth and puffing of lips as signs of animal and human anger. On the painted canvas, rider and horse, their features distorted, are remarkably similar in expression.

The highly imaginative trappings of the painting take the event out of the sphere of the historical and put it into a timeless realm. The cartoon and the copies showing the main scene of the battle were for a long time influential to other artists; to quote the sculptor Benvenuto Cellini, the works became “the school of the world.” Its composition has influenced many painters: from Rubens in the 17th century, who made the most impressive copy of the scene from Leonardo’s now-lost cartoon, to Delacroix in the 19th century.

During this period, Leonardo is believed to have painted Salvator Mundi (c. 1500; “Saviour of the World”), a painting rediscovered in the United States in the early 21st century. Although some experts doubted the piece’s authorship, and the work’s poor condition required extensive conservation, the painting made headlines in 2017 when it sold for a record-breaking $450.3 million at auction. The large sum attested to Leonardo’s enduring celebrity and to his powerful position in the art history canon centuries after his death.

Later painting and drawing

After 1507—in Milan, Rome, and France—Leonardo did very little painting. During his years in Milan he returned to the Leda theme—which had been occupying him for a decade—and probably finished a standing version of Leda about 1513 (the work survives only through copies). This painting became a model of the figura serpentinata (“sinuous figure”)—that is, a figure built up from several intertwining views. It influenced classical artists such as Raphael, who drew it, but it had an equally strong effect on Mannerists such as Jacopo da Pontormo. The drawings he prepared—revealing examples of his late style—have a curious, enigmatic sensuality. Perhaps in Rome he began the painting St. John the Baptist, which he completed in France. Leonardo radically used light and shade to achieve sculptural volume and atmosphere; John emerges from darkness into light and seems to emanate light and goodness. Moreover, in painting the saint’s enigmatic smile, he presented Christ’s forerunner as the herald of a mystic oracle. Leonardo’s was an art of expression that seemed to strive consciously to bring out the hidden ambiguity of the theme. Consummate drawings from this period, such as the Pointing Lady (c. 1516), also are testaments to his undiminished genius.

The last manifestation of Leonardo’s art of expression was in his series of pictorial sketches Visions of the End of the World (c. 1517–18). There Leonardo’s power of imagination—born of reason and fantasy—attained its highest level. Leonardo suggested that the immaterial forces in the cosmos, invisible in themselves, appear in the material things they set in motion. What he had observed in the swirling of water and eddying of air, in the shape of a mountain boulder and in the growth of plants, now assumed gigantic shape in cloud formations and rainstorms. He depicted the framework of the world as splitting asunder, but even in its destruction there occurs—as the monstrously “beautiful” forms of the unleashed elements show—the self-same laws of order, harmony, and proportion that presided at the world’s creation. These rules govern the life and death of every created thing in nature. Without any precedent, these “visions” are the last and most original expressions of Leonardo’s art—an art in which his perception based on saper vedere seems to have come to fruition.

Sculpture of Leonardo da Vinci

Leonardo worked as a sculptor from his youth on, as shown in his own statements and those of other sources. A small group of generals’ heads in marble and plaster, works of Verrocchio’s followers, are sometimes linked with Leonardo, because a lovely drawing attributed to him that is on the same theme suggests such a connection. But the inferior quality of this group of sculpture rules out an attribution to the master. No trace has remained of the heads of women and children that, according to Vasari, Leonardo modeled in clay in his youth.

The two great sculptural projects to which Leonardo devoted himself wholeheartedly were not realized; neither the huge, bronze equestrian statue for Francesco Sforza, on which he worked from about 1489 to 1494, nor the monument for Marshal Trivulzio, on which he was busy in the years 1506–11, were brought to completion. Many sketches of the work exist, but the most impressive were found in 1965 when two of Leonardo’s notebooks—the so-called Madrid Codices—were discovered in the National Library of Madrid. These notebooks reveal the sublimity but also the almost unreal boldness of his conception. Text and drawings both show Leonardo’s wide experience in the technique of bronze casting, but at the same time they reveal the almost utopian nature of the project. He wanted to cast the horse in a single piece, but the gigantic dimensions of the steed presented insurmountable technical problems. Indeed, Leonardo remained uncertain of the problem’s solution to the very end.

The drawings for these two monuments reveal the greatness of Leonardo’s vision of sculpture. Exact studies of the anatomy, movement, and proportions of a live horse preceded the sketches for the monuments; Leonardo even seems to have thought of writing a treatise on the horse. He pondered the merits of two positions for the horse—galloping or trotting—and in both commissions decided in favour of the latter. These sketches, superior in the suppressed tension of horse and rider to the achievements of Donatello’s statue of Gattamelata and Verrocchio’s statue of Colleoni, are among the most beautiful and significant examples of Leonardo’s art. Unquestionably—as ideas—they exerted a very strong influence on the development of equestrian statues in the 16th century.

A small bronze statue of a galloping horseman in Budapest is so close to Leonardo’s style that, if not from his own hand, it must have been done under his immediate influence (perhaps by Giovanni Francesco Rustici). Rustici, according to Vasari, was Leonardo’s zealous student and enjoyed his master’s help in sculpting his large group in bronze, St. John the Baptist Teaching, over the north door of the Baptistery in Florence. There are, indeed, discernible traces of Leonardo’s influence in John’s stance, with the unusual gesture of his upward pointing hand, and in the figure of the bald-headed Levite. While there are few extant examples to study of Leonardo’s sculptural work, the elements of motion and volume he explored in the medium no doubt influenced his drawing and painting, and vice versa.

Architecture

Applying for service in a letter to Ludovico Sforza, Leonardo described himself as an experienced architect, military engineer, and hydraulic engineer; indeed, he was concerned with architectural matters all his life. But his effectiveness was essentially limited to the role of an adviser. Only once—in the competition for the cupola of the Milan cathedral (1487–90)—did he actually consider personal participation, but he gave up this idea when the model he had submitted was returned to him. In other instances, his claim to being a practicing architect was based on sketches for representative secular buildings: for the palace of a Milanese nobleman (about 1490), for the villa of the French governor in Milan (1507–08), and for the Medici residence in Florence (1515). Finally, there was his big project for the palace and garden of Romorantin in France (1517–19). Especially in this last project, Leonardo’s pencil sketches clearly reveal his mastery of technical as well as artistic architectural problems; the view in perspective gives an idea of the magnificence of the site.

But what really characterizes and immortalized Leonardo’s architectural studies is their comprehensiveness; they range far afield and embrace every type of building problem of his time and even involve urban planning. Furthermore, there frequently appears evidence of Leonardo’s impulse to teach: he wanted to collect his writings on this theme in a theory of architecture. This treatise on architecture—the initial lines of which are in Codex B in the Institut de France in Paris, a model book of the types of sacred and profane buildings—was to deal with the entire field of architecture as well as with the theories of forms and construction and was to include such items as urbanism, sacred and profane buildings, and a compendium of important individual elements (for example, domes, steps, portals, and windows).

In the fullness and richness of their ideas, Leonardo’s architectural studies offer an unusually wide-ranging insight into the architectural achievements of his epoch. Like a seismograph, his observations sensitively register all themes and problems. For almost 20 years he was associated with Bramante at the court of Milan and again met him in Rome in 1513–14; he was closely associated with other distinguished architects, such as Francesco di Giorgio, Giuliano da Sangallo, Giovanni Antonio Amadeo, and Luca Fancelli. Thus, he was brought in closest touch with all of the most-significant building undertakings of the time. Since Leonardo’s architectural drawings extend over his whole life, they span precisely that developmentally crucial period—from the 1480s to the second decade of the 16th century—in which the principles of the High Renaissance style were formulated and came to maturity. That this genetic process can be followed in the ideas of one of the greatest men of the period lends Leonardo’s studies their distinctive artistic value and their outstanding historical significance.

Science of painting

Leonardo’s advocacy of a science of painting is best displayed in his notebook writings under the general heading “On Painting.” The notebooks provide evidence that, among many projects he planned, he intended to write a treatise discussing painting. After inheriting Leonardo’s vast manuscript legacy in 1519, it is believed that, sometime before 1542, Melzi extracted passages from them and organized them into the Trattato della pittura (“Treatise on Painting”) that is attributed to Leonardo. Only about a quarter of the sources for Melzi’s manuscript—known as the Codex Urbinas, in the Vatican Library—have been identified and located in the extant notebooks, and it is impossible to assess how closely Melzi’s presentation of the material reflected Leonardo’s specific intentions.

Abridged copies of Melzi’s manuscript appeared in Italy during the late 16th century, and in 1651 the first printed editions were published in French and Italian in Paris by Raffaelo du Fresne, with illustrations after drawings by Nicolas Poussin. The first complete edition of Melzi’s text did not appear until 1817, published in Rome. The two standard modern editions are those of Emil Ludwig (1882; in 3 vol. with German translation) and A. Philip McMahon (1956; in 2 vol., a facsimile of the Codex Urbinas with English translation).

Despite the uncertainties surrounding Melzi’s presentation of Leonardo’s ideas, the passages in Leonardo’s extant notebooks identified with the heading “On Painting” offer an indication of the treatise Leonardo had in mind. As was customary in treatises of the time, Leonardo planned to combine theoretical exposition with practical information, in this case offering practical career advice to other artists. But his primary concern in the treatise was to argue that painting is a science, raising its status as a discipline from the mechanical arts to the liberal arts. By defining painting as “the sole imitator of all the manifest works of nature,” Leonardo gave essential significance to the authority of the eye, believing firmly in the importance of saper vedere. This was the informing idea behind his defense of painting as a science.

In his notebooks Leonardo pursues this defense through the form of the paragone (“comparison”), a disputation that advances the supremacy of painting over the other arts. He roots his case in the function of the senses, asserting that “the eye deludes itself less than any of the other senses,” and thereby suggests that the direct observation inherent in creating a painting has a truthful, scientific quality. After asserting that the useful results of science are “communicable,” he states that painting is similarly clear: unlike poetry, he argues, painting presents its results as a “matter for the visual faculty,” giving “immediate satisfaction to human beings in no other way than the things produced by nature herself.” Leonardo also distinguishes between painting and sculpture, claiming that the manual labour involved in sculpting detracts from its intellectual aspects, and that the illusionistic challenge of painting (working in two rather than three dimensions) requires that the painter possess a better grasp of mathematical and optical principles than the sculptor.

In defining painting as a science, Leonardo also emphasizes its mathematical basis. In the notebooks he explains that the 10 optical functions of the eye (“darkness, light, body and colour, shape and location, distance and closeness, motion and rest”) are all essential components of painting. He addresses these functions through detailed discourses on perspective that include explanations of perspectival systems based on geometry, proportion, and the modulation of light and shade. He differentiates between types of perspective, including the conventional form based on a single vanishing point, the use of multiple vanishing points, and aerial perspective. In addition to these orthodox systems, he explores—via words and geometric and analytic drawings—the concepts of wide-angle vision, lateral recession, and atmospheric perspective, through which the blurring of clarity and progressive lightening of tone is used to create the illusion of deep spatial recession. He further offers practical advice—again through words and sketches—about how to paint optical effects such as light, shadow, distance, atmosphere, smoke, and water, as well as how to portray aspects of human anatomy, such as human proportion and facial expressions.

Anatomical studies and drawings of Leonardo da Vinci

Leonardo’s fascination with anatomical studies reveals a prevailing artistic interest of the time. In his own treatise Della pittura (1435; “On Painting”), theorist Leon Battista Alberti urged painters to construct the human figure as it exists in nature, supported by the skeleton and musculature, and only then clothed in skin. Although the date of Leonardo’s initial involvement with anatomical study is not known, it is sound to speculate that his anatomical interest was sparked during his apprenticeship in Verrocchio’s workshop, either in response to his master’s interest or to that of Verrocchio’s neighbor Pollaiuolo, who was renowned for his fascination with the workings of the human body. It cannot be determined exactly when Leonardo began to perform dissections, but it might have been several years after he first moved to Milan, at the time a centre of medical investigation. His study of anatomy, originally pursued for his training as an artist, had grown by the 1490s into an independent area of research. As his sharp eye uncovered the structure of the human body, Leonardo became fascinated by the figura istrumentale dell’ omo (“man’s instrumental figure”), and he sought to comprehend its physical working as a creation of nature. Over the following two decades, he did practical work in anatomy on the dissection table in Milan, then at hospitals in Florence and Rome, and in Pavia, where he collaborated with the physician-anatomist Marcantonio della Torre. By his own count Leonardo dissected 30 corpses in his lifetime.

Leonardo’s early anatomical studies dealt chiefly with the skeleton and muscles; yet even at the outset, Leonardo combined anatomical with physiological research. From observing the static structure of the body, Leonardo proceeded to study the role of individual parts of the body in mechanical activity. This led him finally to the study of the internal organs; among them he probed most deeply into the brain, heart, and lungs as the “motors” of the senses and of life. His findings from these studies were recorded in the famous anatomical drawings, which are among the most significant achievements of Renaissance science. The drawings are based on a connection between natural and abstract representation; he represented parts of the body in transparent layers that afford an “insight” into the organ by using sections in perspective, reproducing muscles as “strings,” indicating hidden parts by dotted lines, and devising a hatching system. The genuine value of these dimostrazione lay in their ability to synthesize a multiplicity of individual experiences at the dissecting table and make the data immediately and accurately visible; as Leonardo proudly emphasized, these drawings were superior to descriptive words. The wealth of Leonardo’s anatomical studies that have survived forged the basic principles of modern scientific illustration. It is worth noting, however, that during his lifetime, Leonardo’s medical investigations remained private. He did not consider himself a professional in the field of anatomy, and he neither taught nor published his findings.

Although he kept his anatomical studies to himself, Leonardo did publish some of his observations on human proportion. Working with the mathematician Luca Pacioli, Leonardo considered the proportional theories of Vitruvius, the 1st-century-BCE Roman architect, as presented in his treatise De architectura (“On Architecture”). Imposing the principles of geometry on the configuration of the human body, Leonardo demonstrated that the ideal proportion of the human figure corresponds with the forms of the circle and the square. In his illustration of this theory, the so-called Vitruvian Man, Leonardo demonstrated that when a man places his feet firmly on the ground and stretches out his arms, he can be contained within the four lines of a square, but when in a spread-eagle position, he can be inscribed in a circle.

Leonardo envisaged the great picture chart of the human body he had produced through his anatomical drawings and Vitruvian Man as a cosmografia del minor mondo (“cosmography of the microcosm”). He believed the workings of the human body to be an analogy, in microcosm, for the workings of the universe. Leonardo wrote: “Man has been called by the ancients a lesser world, and indeed the name is well applied; because, as man is composed of earth, water, air, and fire…this body of the earth is similar.” He compared the human skeleton to rocks (“supports of the earth”) and the expansion of the lungs in breathing to the ebb and flow of the oceans.

Mechanics and cosmology

According to Leonardo’s observations, the study of mechanics, with which he became quite familiar as an architect and engineer, also reflected the workings of nature. Throughout his life Leonardo was an inventive builder; he thoroughly understood the principles of mechanics of his time and contributed in many ways to advancing them. The two Madrid notebooks deal extensively with his theory of mechanics; the first was written in the 1490s, and the second was written between 1503 and 1505. Their importance lay less in their description of specific machines or work tools than in their use of demonstration models to explain the basic mechanical principles and functions employed in building machinery. As in his anatomical drawings, Leonardo developed definite principles of graphic representation—stylization, patterns, and diagrams—that offer a precise demonstration of the object in question.

Leonardo was also quite active as a military engineer, beginning with his stay in Milan. But no definitive examples of his work can be adduced. The Madrid notebooks revealed that, in 1504, probably sent by the Florentine governing council, he stood at the side of the lord of Piombino when the city’s fortifications system was repaired and suggested a detailed plan for overhauling it. His studies for large-scale canal projects in the Arno region and in Lombardy show that he was also an expert in hydraulic engineering.

Leonardo was especially intrigued by problems of friction and resistance, and with each of the mechanical elements he presented—such as screw threads, gears, hydraulic jacks, swiveling devices, and transmission gears—drawings took precedence over the written word. Throughout his career he also was intrigued by the mechanical potential of motion. This led him to design a machine with a differential transmission, a moving fortress that resembles a modern tank, and a flying machine. His “helical airscrew” (c. 1487) almost seems a prototype for the modern helicopter, but, like the other vehicles Leonardo designed, it presented a singular problem: it lacked an adequate source of power to provide propulsion and lift.

Wherever Leonardo probed the phenomena of nature, he recognized the existence of primal mechanical forces that govern the shape and function of the universe. This is seen in his studies of the flight of birds, in which his youthful idea of the feasibility of a flying apparatus took shape and which led to exhaustive research into the element of air; in his studies of water, the vetturale della natura (“conveyor of nature”), in which he was as much concerned with the physical properties of water as with its laws of motion and currents; in his research on the laws of growth of plants and trees, as well as the geologic structure of earth and hill formations; and, finally, in his observation of air currents, which evoked the image of the flame of a candle or the picture of a wisp of cloud and smoke. In his drawings based on the numerous experiments he undertook, Leonardo found a stylized form of representation that was uniquely his own, especially in his studies of whirlpools. He managed to break down a phenomenon into its component parts—the traces of water or eddies of the whirlpool—yet at the same time preserve the total picture, creating both an analytic and a synthetic vision.

Leonardo as artist-scientist

As the 15th century expired, Scholastic doctrines were in decline, and humanistic scholarship was on the rise. Leonardo, however, was part of an intellectual circle that developed a third, specifically modern, form of cognition. In his view, the artist—as transmitter of the true and accurate data of experience acquired by visual observation—played a significant part. In an era that often compared the process of divine creation to the activity of an artist, Leonardo reversed the analogy, using art as his own means to approximate the mysteries of creation, asserting that, through the science of painting, “the mind of the painter is transformed into a copy of the divine mind, since it operates freely in creating many kinds of animals, plants, fruits, landscapes, countrysides, ruins, and awe-inspiring places.” With this sense of the artist’s high calling, Leonardo approached the vast realm of nature to probe its secrets. His utopian idea of transmitting in encyclopaedic form the knowledge thus won was still bound up with medieval Scholastic conceptions; however, the results of his research were among the first great achievements of the forthcoming age’s thinking, because they were based to an unprecedented degree on the principle of experience.

Finally, although he made strenuous efforts to become erudite in languages, natural science, mathematics, philosophy, and history, as a mere listing of the wide-ranging contents of his library demonstrates, Leonardo remained an empiricist of visual observation. It is precisely through this observation—and his own genius—that he developed a unique “theory of knowledge” in which art and science form a synthesis. In the face of his overall achievements, therefore, the question of how much he finished or did not finish becomes pointless. The crux of the matter is his intellectual force—self-contained and inherent in every one of his creations—a force that continues to spark scholarly interest today. In fact, debate has spilled over into the personal realm of his life—over his sexuality, religious beliefs, and even possible vegetarianism, for example—which only confirms and reflects what has long been obvious: whether the subject is his life, his ideas, or his artistic legacy, Leonardo’s influence shows little sign of abating.