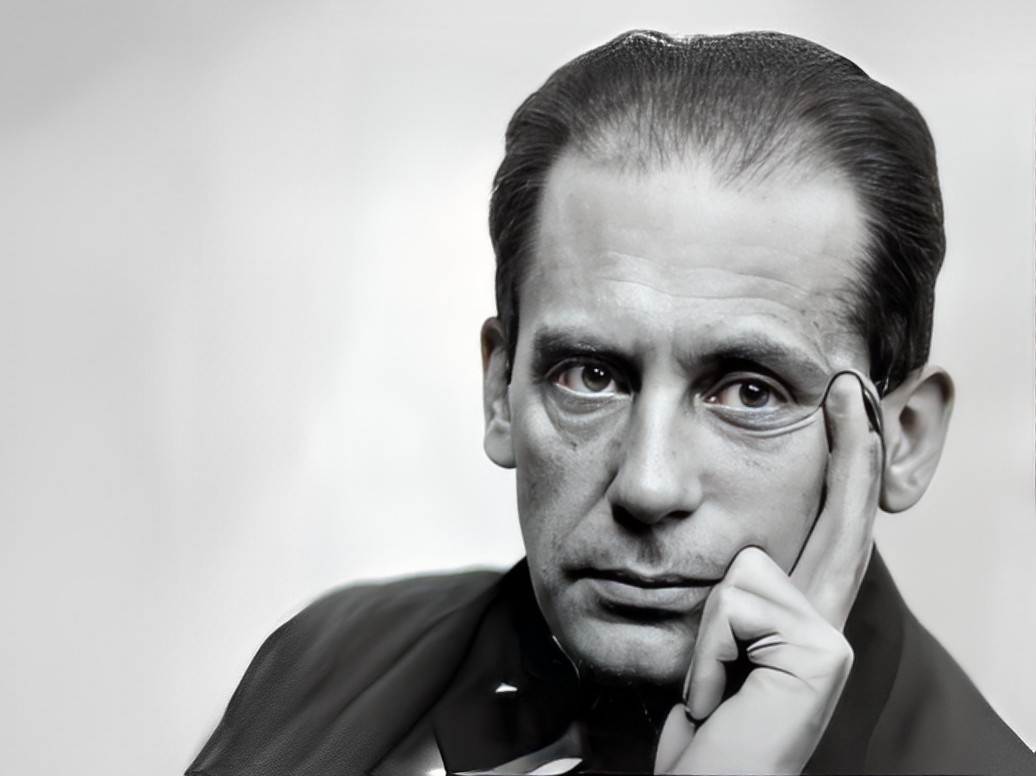

Walter Gropius

Walter Gropius

United States of America

United States of America German Empire

German EmpireWalter Gropius, in full Walter Adolph Gropius, (born May 18, 1883, Berlin, Ger.—died July 5, 1969, Boston, Mass., U.S.), German American architect and educator who, particularly as director of the Bauhaus (1919–28), exerted a major influence on the development of modern architecture. His works, many executed in collaboration with other architects, included the school building and faculty housing at the Bauhaus (1925–26), the Harvard University Graduate Center, and the United States Embassy in Athens.

Gropius, the son of an architect father, studied architecture at the technical institutes in Munich (1903–04) and in Berlin–Charlottenburg (1905–07). He worked briefly in an architectural office in Berlin (1904) and saw military service (1904–05). Before completing school he built his first buildings, farm labourers’ cottages in Pomerania (1906). For a year he traveled in Italy, Spain, and England, and in 1907 he joined the office of the architect Peter Behrens in Berlin.

Gropius acknowledged that his work with Behrens and the design problems he undertook for a German electricity company did much to shape his lifelong interest in progressive architecture and the interrelationship of the arts. From the time he left Behrens in 1910 until 1914, Gropius developed a clear commitment to and talent for organization and a dedication to promoting his ideas on the arts. In 1911 he became a member of the German Labour League (Deutscher Werkbund), which had been founded in 1907 to ally creative designers with machine production. Gropius argued for such building techniques as prefabrication of parts and assembly on the site. However much he accepted the inevitability and restrictions of mechanization, he felt it was up to the artistically trained designer to “breathe a soul into the dead product of the machine.” He was against imitation, snobbery, and dogma in the arts and cautioned against such oversimplification as the notion that the function of a product should determine its appearance.

Gropius’ growing intellectual leadership was complemented by his design of two significant buildings, both done in collaboration with Adolph Meyer: the Fagus Works at Alfeld-an-der-Leine (1911) and the model office and factory buildings in Cologne (1914) done for the Werkbund Exposition. The Fagus Works, bolder than any of Behrens’ works, is marked by large areas of glass wall broken by visible steel supports, the whole done with little affectation. The Cologne buildings were more formal, some say influenced by the American architect Frank Lloyd Wright. Together these two buildings testify to Gropius’ design maturity prior to World War I.

During that war Gropius served as a cavalry officer on the Western Front, was wounded, and received the Iron Cross for bravery. In 1915 he married a widow, Alma (Schindler) Mahler, whom he had met in 1910 when she was still married to the Austrian composer Gustav Mahler. Their wartime marriage, dependent on furloughs, was complicated by her affair with the German author Franz Werfel, and they were divorced in 1919. Their only child, Alma Manon, died in 1935.

Bauhaus period

Even before the end of the war, the city of Weimar approached Gropius for his ideas on art education. In April 1919 he became director of the Grand Ducal Saxon School of Arts and Crafts, the Grand Ducal Saxon Academy of Arts, and the Grand Ducal Saxon School of Arts, which were immediately united as Staatliches Bauhaus Weimar (“Public Bauhaus Weimar”). Gropius’ acceptance of this appointment was the most decisive step in his career. With his temperament for the practical world of art, politics, and administration, Gropius succeeded in establishing a viable new approach to design education, one that became an international prototype and eventually supplanted the 200-year-old supremacy of the French École des Beaux-Arts.

A key tenet of Gropius’ Bauhaus teaching was the requirement that the architect and designer undergo a practical crafts training to acquaint himself with materials and processes. Although the program was to have been a comprehensive one, budget limitations permitted only a portion of the crafts shops to open. No formal study of architecture was offered at Weimar. Despite the early Werkbund principle of joining art with industry, much activity centred on handicrafts, such as ceramics, weaving, and stained-glass design. Many painters and sculptors joined the staff: Paul Klee, Lyonel Feininger, Wassily Kandinsky, Gerhard Marcks, and, later, László Moholy-Nagy and Josef Albers—altogether an astonishing roster of artists.

Somehow it did not seem incongruous for artists to be teaching applied design. As an introduction to design principles, a beginning course, Vorkurs, was developed by the Swiss painter and sculptor Johannes Itten, which itself became the most widely copied aspect of the Bauhaus curriculum. Students explored two- and three-dimensional design using a variety of simple materials, such as wire, wood, and paper. The psychological effects of form, colour, and texture were studied as well. Although his instructors were gifted, it was Gropius’ own persistence that made this educational experiment work.

Historians disagree on the character of the early Bauhaus years. Certainly in 1919–22 Bauhaus students were allowed to express subjective feelings in their art; individuality and expressionism were not uncommon. The prewar Gropius belief that art must conform to and express the economic character and rational order of modern society seemed to be submerged in a new belief that the greatness of art stood above utilitarian considerations. A reverse shift came in 1922, not without controversy; Itten left, and a more rational and objective approach returned. The individually made products were intended as prototypes for machine production, and some designs were produced commercially. They emphasized geometrical forms, smooth surfaces, regular outlines, primary colours, and modern materials—all of which, to many eyes, epitomized impersonality in art. It is this last phase of Bauhaus output that is publicly accepted as characteristic of Bauhaus “style,” although Gropius himself disdained the use of the word “concept.”

Gropius saw architecture and design as ever changing, always related to the contemporary world. He spoke of the architect’s duty to encompass the total visual environment. He himself designed furniture, a railroad car, and an automobile. He emphasized housing and city planning, the usefulness of sociology, and the necessity of using teams of specialists.

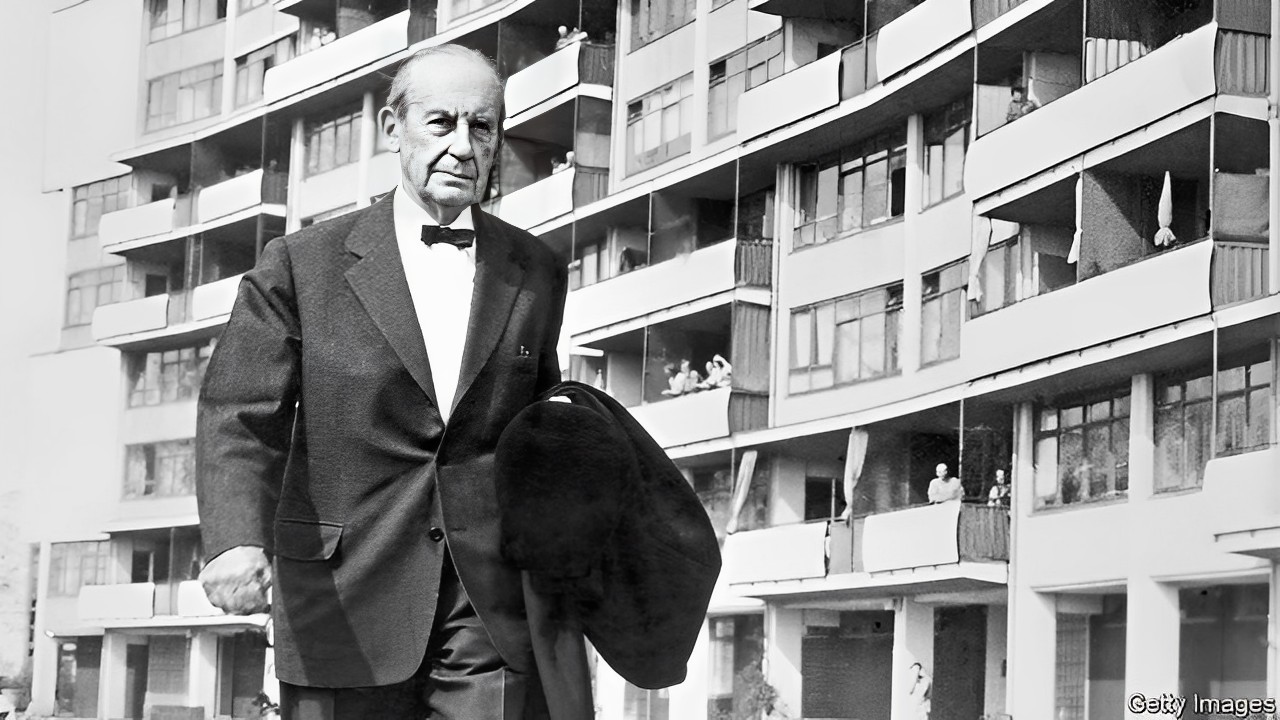

In 1925 the Bauhaus moved to Dessau with the promise of better financial support and an escape from the growing antagonism of the conservative Weimar community. In Dessau, Gropius designed the school building and faculty housing (1925–26). The school itself is a key monument of modern architecture and Gropius’ best-known building. Its dynamic composition, asymmetrical plan, smooth white walls set with horizontal windows, and flat roof are features associated with the so-called International Style of the 1920s. Gropius resigned as director of the Bauhaus in 1928 to return to practice privately as an architect in Berlin. During 1929–30 he designed a portion of a housing colony in Berlin–Siemensstadt. Gropius’ regular facades of enormous length, together with a rigid orientation, illustrate an excessively intellectual solution with a “curse of uniformity,” which Gropius himself decried in later years.

Harvard years of Walter Gropius

Unsympathetic to the Nazi regime, he and his second wife, Ise Frank, whom he had married in 1923, left Germany secretly via Italy for exile in England in 1934. Hitler’s government closed the Bauhaus in 1933. Gropius’ brief time in England was marked by collaboration with the architect Maxwell Fry that resulted in their important work, Village College at Impington, Cambridgeshire (1936).

In February 1937 Gropius arrived in Cambridge, Mass., to become professor of architecture at Harvard University. The following year he was made chairman of the department, a post he held until his retirement in 1952. He became a naturalized U.S. citizen in 1944. At Harvard he introduced the Bauhaus philosophy of design into the curriculum, although he was unable to implement workshop training. He was also unsuccessful in abolishing the history of architecture as a course. His crusade for modern design, however, was immediately popular among the students. His innovations at Harvard soon provoked similar educational reform in other architectural schools in the United States and marked the beginning of the end of a historically imitative architecture in that country.

In addition to his teaching, Gropius collaborated with Marcel Breuer, a former Bauhaus pupil and later fellow teacher, from 1937 until 1940. Among their designs was Gropius’ own house in Lincoln, Mass., which, with its use of white-painted wood and fieldstone, restated New England traditionalism in modern terms. This house and others designed by them were controversial, but the architects lived to see acceptance of their ideas. In 1942 Gropius renewed his interest in the production of architecture by industry when he became the vice president of General Panel Corporation, a company that made prefabricated housing. He retired in 1952.

In 1946, with six of his former Harvard pupils as partners, Gropius formed The Architects Collaborative (TAC), based in Cambridge. Among its varied American and international commissions, TAC received one to do the Harvard University Graduate Center (1949–50), a grouping of dormitory buildings and dining commons. The design is reminiscent of but less forceful than the Dessau Bauhaus buildings. Other TAC designs include the United States Embassy in Athens (1960) and the University of Baghdad (design accepted 1960, still under construction). Gropius remained an active member of TAC until he died at the age of 86. In accord with his request made in 1933 that his funeral not be a mournful affair but marked in a festive manner, 70 friends in Cambridge drank champagne in his memory two days after his death.

Most assessments of Gropius’ influential career centre upon his achievements as educator and author rather than as architect. In his own building designs he turned away from personal and subjective aspects in favour of reaching for intellectual solutions of larger and socially urgent problems. Among his most important ideas was his belief that all design—whether of a chair, a building, or a city—should be approached in essentially the same way: through a systematic study of the particular needs and problems involved, taking into account modern construction materials and techniques, without reference to previous forms or styles.

His architecture does not have the aesthetic fascination of Wright’s or Le Corbusier’s but reflects a sober and programmatic concern that marked his whole life. Yet always, in conversation and criticism, he reminded his pupils of the vitality of the individual spirit, of the spontaneity of life itself. His habit of wearing a beret with a business suit was perhaps symbolic of the two worlds he hoped to bridge, “the gap between the rigid mentality of the businessman and technologist and the imagination of the creative artist.”